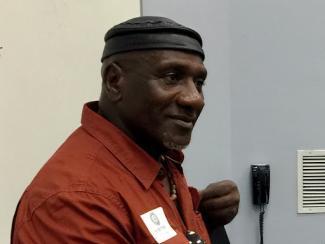

In 1974, 16-year-old Gary Tyler was unjustifiably blamed for a white teenager’s death after white attackers mobbed a bus of Black students. His arrest came after simply talking back to police. He wasn’t released from Angola prison until 2016.

But he left there with an incredible talent.

Tyler grew up with women in his family who sewed, but he didn’t learn until he was incarcerated. He made quilts for various fundraising efforts, joining a rich Black cultural tradition. Now, in 2023, he works to support unhoused youth and is beginning his first solo art exhibition.

And while the media, an all-white jury, and the prison system once thought him so threatening he deserved the death penalty, Tyler’s pieces reclaim his story, rendering their anti-Black narratives illegitimate.

Some of the quilts depict Tyler and his political prisoner friends surviving captivity. Others display beautiful butterflies, likening Tyler’s release from prison to escaping a cocoon.

Still, Tyler doesn’t want his audience to mistake his rich textiles for a desire to be defined by unjust incarceration. He’s more than that.

“I’m interested in what I am becoming,” he says.

From quilts and recipes to even dancing and memes, the ways we express ourselves exhibit the resounding truth of our personhood.

Like Tyler, we may be remembered for surviving despite literal and metaphorical prisons of anti-Blackness. But they don’t define us. We define ourselves.